Understanding a Hidden Winter Hazard

Ultimately, “safe ice” on Lake Minnetonka is not a fixed condition but a temporary and highly localized one, ice is never 100% safe

I’m not one to venture out on the ice. I don’t go snowmobiling anymore and have never been an ice fisherman. I just don’t like winter. I don’t like the cold and I don’t care for snow either. I guess I can tolerate snow from Christmas Eve to New Year’s day, then I’ve had my fill of it for the year. But a lot of you do like the cold, the snow and recreation on a frozen lake so this post is for you.

We always hear about somebody breaking through every year, and sometimes breaking through turns fatal. It seems to me I remember a few years ago, right around this time, near Christmas, a family’s life was changed forever, and I’d sure hate to hear about that happening again.

So let’s talk about the ice.

Despite appearing solid and familiar, Lake Minnetonka is one of the most complex and potentially dangerous lakes in the state when it comes to ice safety.

Rather than a single open basin, the lake is a network of bays, channels, narrows, and connecting waterways. These areas experience constant variations in water movement, which directly affect ice formation. Channels and narrows freeze later, thaw sooner, and can contain dangerously thin ice even during prolonged cold periods. Springs, aeration systems, underwater obstructions, and wind-driven currents further weaken ice from below, often without visible warning.

Because of this complexity, ice conditions on Lake Minnetonka can change dramatically over short distances. A stretch of solid ice may exist only feet away from an area that cannot support a person’s weight.

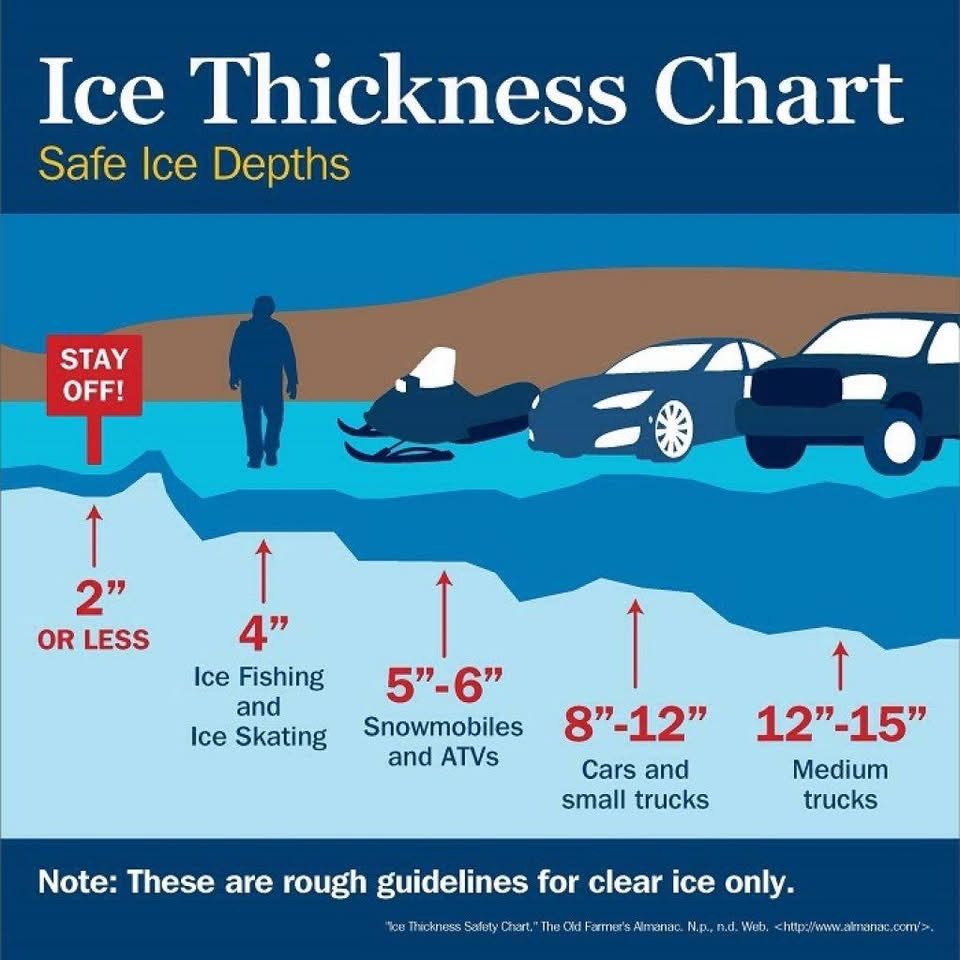

Statewide guidelines from the Minnesota DNR provide a general framework for understanding ice strength. Roughly four inches of clear, solid ice is considered the minimum for a person on foot, with greater thickness required for snowmobiles and vehicles (see chart below). However, these benchmarks are not assurances of safety. On a lake as dynamic as Minnetonka, a single measurement—or reliance on reports from another bay—can be misleading. Ice must be checked repeatedly and continuously as conditions shift.

Ice quality is as important as thickness. Clear, blue or black ice is far stronger than white or cloudy ice, which often contains trapped air or refrozen snow. Snow cover insulates ice from cold air, slowing thickening and concealing weak spots. Late in the season, sunlight and warming temperatures degrade ice from the surface downward, increasing the risk of sudden failure.

Human activity also contributes to a false sense of security. Tracks from vehicles, plowed ice roads, and clustered fishing houses can make an area appear safe long after conditions have deteriorated. Each winter, vehicles break through the ice on the lake often in places that were previously considered reliable. Pressure ridges and cracks can form rapidly, especially after temperature swings, further destabilizing the ice.

Experienced winter users emphasize preparation and caution. Carrying ice picks, wearing flotation gear, traveling with a partner, and informing others of travel plans are basic safety measures. Avoiding channels, narrows, marinas, docks, and bridge areas is essential.

Ultimately, “safe ice” on Lake Minnetonka is not a fixed condition but a temporary and highly localized one. Conditions can change overnight or within hours. The safest decision is guided by current local knowledge, careful on-site assessment, and a willingness to turn back when uncertainty arises. Respect for Lake Minnetonka’s winter hazards is not merely prudent—it can be lifesaving.